The “Modern Lives” project provided a comparative study of sexuality, new media and Christianity in three African cities, and their entanglements with the cultural processes we usually term globalisation. Funded by Leverhulme Trust between 2008 and 2011, the project formed an innovative re-conceptualisation of the relationship between sexuality, culture and social change in Africa.

Published: Monday 20 September, 2010

The “Modern Lives” project provided a comparative study of sexuality, new media and Christianity in three African cities, and their entanglements with the cultural processes we usually term globalisation. Funded by Leverhulme Trust between 2008 and 2011, the project formed an innovative re-conceptualisation of the relationship between sexuality, culture and social change in Africa.

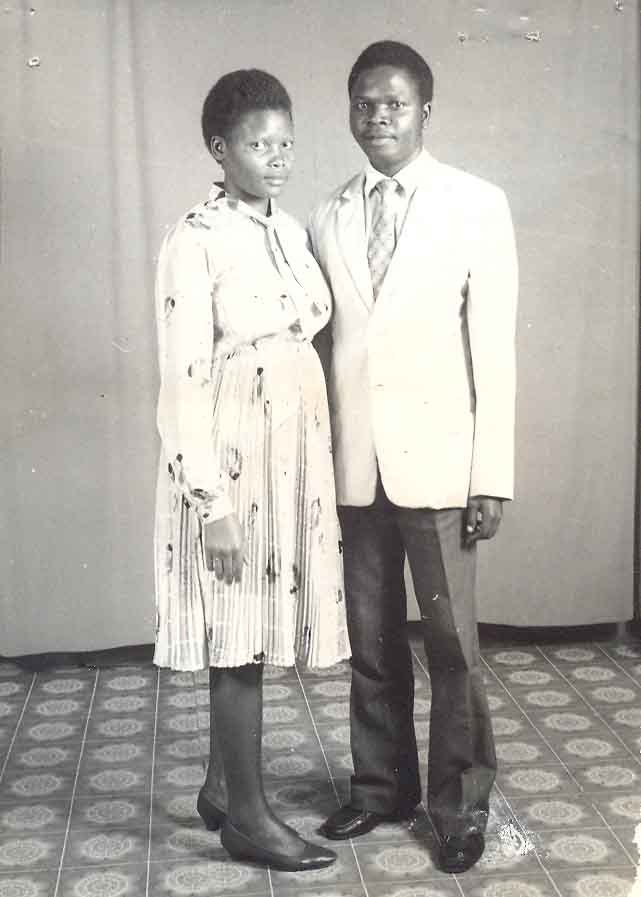

Both in the academy and in the world of international development, recent studies of sexuality in Africa have been dominated by a Foucauldian framework that assumes sexual practices and beliefs as culturally determined, and therefore regulated by different moral concerns than in the west. Departing from this view, Modern Lives reconsidered the debate on sexuality in Africa by exploring how individual women and men understand and live their intimate lives, and how they experience, manage and comprehend the fact that sexuality links the most intimate spheres of everyday life, one’s experience of one’s own body, and that of others, to economic and political structures and their transformation.

The project undertook extensive new research in Nairobi, Kampala and Lusaka, as well as revisited Professor Moore’s anthropological research on sex, gender and sexuality in Africa over the past thirty years. Nairobi, Lusaka and Kampala are significant cities for having burgeoning professional middle classes, with large cohorts of young, cosmopolitan professionals now dominating the workplace. Urban middle classes in Africa remain under-researched in anthropology, and Modern Lives provided a detailed study of a significant emerging political and social force. In all three cities the study investigated the lifestyles, relationships, and desires of several demographic cohorts: university students, young professionals, parents, couples attending Christian pre-marriage counselling, and gay and lesbian activist groups.

There were three main strands to this research:

– Sexuality and Culture

Founded in a critique of widespread scholarship on Africa that sees sexual attitudes and behaviours as a consequence of culture, this strand revealed how this problematic perspective has resulted in an impasse in the analysis of social change in Africa. Taking lived historical experiences as a starting point, Modern Lives set out to unravel the relevance of a concept of sexuality to the lives of Kenyan, Zambian and Ugandan men and women.

The study encouraged participants to reflect on their lifestyles, desires and aspirations. For example, university students discussed campus life, in particular the formations of new identities away from the parental home, their negotiations around intimacy and sex, the role of religion in relationships and university life more broadly, and their aspirations for their future choices, careers and marriages. Young professionals reflected on their intimate lives in urban centres, their links to their parents’ rural communities, their perspectives on what it means to be Kenyan or African. We also undertook extensive research with couples attending pre-marital counselling (a common requirement for marriage in many churches in Nairobi and Kampala). Research with couples at two Anglican Cathedrals and two Pentecostal churches highlighted expectations for marriage and sexual lives, inter-cultural relationships, as well as Christian churches’ increasing concern with the intimate lives of their congregations.

This fieldwork provided new insights on three key aspects of sexuality: firstly, the constitution of sexuality as a separate moral realm, ideas about the management of sexual practice and the emergence of new forms of desire; secondly, the development of sexuality as a core component of modern subjectivities and concepts of the self; and thirdly, the transformation of private and family life, and desire for a level of autonomy in conjugal relations and matters of community, culture and lineage.

– Technology and the Media

This strand explored how relatively new technologies (such as mobile phones, the internet and social media) as well as rapidly expanding access to print media, (radio, music and television) intersect with the changing nature of love, intimacy and marriage. Over the past fifteen years, state control of the media in Kenya, Zambia and Uganda has considerably loosened and access to broadband and 3G connectivity has soared. This has stimulated a surge in public consumption of, and often participation, lifestyle magazines, newspaper supplements, FM radio, TV chatshows, new music, Facebook, Twitter and blogs.

One notable consequence has been the way that the constitution of the self now takes place in a more public sphere, and explicitly encourages self-reflection and choice. Phoning in to a radio station, creating a Facebook profile, even blogging about recent events all require the participant to curate how they want to portray themselves as they create a public persona remote from their physical self. Such participatory media formats also make public things that would previously have remained intimate affairs. Radio chat shows and phone-ins are used both to seek and distribute advice on relationships, sex and desire as well as provide news and entertainment, thus linking personal and public concerns. As people seek to understand their most intimate moments, such experiences are inextricably linked to wider social and political transformations.

Sexual identities and national politics

The third strand followed the changing politics of sexual identity with the rise of LGBT advocacy and activism in all three countries. Research on this strand began about a year before the emergence of the now notorious anti-homosexuality bill in Uganda, which aimed to drastically increase the penalties for participating in or condoning same-sex relationships. It was thus an alarming but also revealing time to be explore the nexus of sexual preference and national politics, reflecting the myriad ways in which intimate lives are drawn into national and international debates over human rights, globalisation and sovereignty. The bill has proved a rallying point for many individuals – in Uganda and beyond – and has forced new considerations of the significance and meaning of sexual identity.

This research revealed how, as the battle lines hardened between those for and against the bill, so to did affiliations of sexuality. At the outset of our research, many participants viewed their sexual relations as a personal private choice, not a specific public identity with which they needed to be affiliated: many actively resisted labels such as gay, straight or bi. Hostile state politics, backed up by the support of some extreme evangelical churches in Africa and in the United States, have in part forced an either/or sexual identification to the fore. But importantly, so too have international development and human rights organisations seeking to assist ‘LGBT’ activist groups in coping with ‘anti-homosexual’ campaigns and crackdowns. Coming out as lesbian, gay, bi or transgender was thus very dangerous, attracting hostility and even violence, but on the other hand could offer a degree of protection, and even an avenue into a transnational community of activists.

***

Central to Modern Lives were the contributions of many young researchers. In partnership with the British Institute in Eastern Africa, the Modern Lives project worked with and provided social science fieldwork training for young scholars from East Africa and the UK. These included Constance Smith, Gordon Omenya, Hannah Elliott, Elizabeth Njogu, Zoe Cormack, Amon Mwiine Ashaba, Monica Agena, Jovah Katushabe, Magnus Taylor, Paul Kipchumba and Ricardo Munyegera.

Modern Lives was funded by the Leverhulme Trust and supported by the British Institute in Eastern Africa.