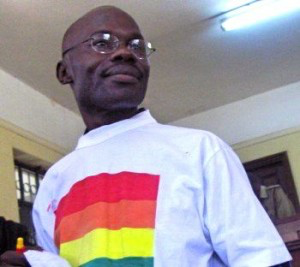

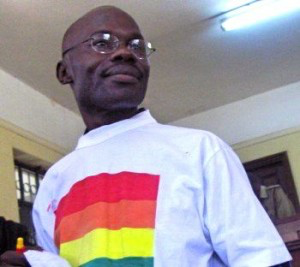

When the LGBTI activist David Kato was murdered last month, newspapers carried worldwide condemnation of the act. Advocacy organisations issued statements, as did President Obama, Hillary Clinton and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

David – and his friends and colleagues – first found themselves the subjects of media attention in 2009 when David Bahati introduced a private members bill into the Ugandan Parliament seeking to add the death penalty to existing laws criminalising homosexuality. Then, in 2010, a local Ugandan newspaper published the photographs and personal details of LGBTI activists with the slogan ‘hang them’ blazoned across the front page. David and other members of the Ugandan LGBTI community successfully brought a case against the newspaper and won a ruling from the Ugandan High Court in January of this year safeguarding all Ugandans’ ‘rights to privacy and the preservation of human dignity’. David’s own situation ultimately proved tragically vulnerable, but surely the outpouring of protest at this death, the swiftness and global character of its condemnation, must mean that we can be sure of the strength of political commitment recognising the fundamental rights of LGBTI individuals around the world.

In a published statement, Hilary Clinton said ‘our ambassadors and diplomats around the world will continue to advance a comprehensive human rights policy, and to stand with those who, with their courage, make the world a more just place where every person can live up to his or her God-given potential’. The role of God and the recognition he or she confers has played a troubling role in David’s death, in the events leading up to it and in the responses it has provoked. Early, last year, three American Evangelical leaders arrived in Uganda to give a series of lectures about the ‘evils’ of being gay and how to be ‘cured’. Unsurprisingly, the individuals involved are now distancing themselves from the fact that their visit prompted a flood of hate speech at the time, and denying any responsibility for David’s death. Conflicting reports may or may not have exaggerated the content of their remarks, but the outcome was a series of publically attributed statements in Uganda about the gay movement as an ‘evil institution’ that seeks to defeat marriage, and sodomise and recruit African children. Their insistence on Christian condemnation of homosexuality was whipped up into a furore after a local Ugandan pastor Martin Ssempa began to address crowds and mobilise anti-gay sentiment by showing hard-core gay pornography accompanied by puerile and loathsome commentary. Ordinary churchgoers who attended these rallies were visibly shocked and some reportedly reduced to tears by his virulent homophobia, designed to garner support for the anti-homosexuality bill. Ssempa’s evident fascination with his own unmanaged feelings of disgust frightened many. ‘Anal licking – that’s what they are doing in the privacy of their bedrooms ‘’ heterosexuals do not eat poop – that’s an abomination. It’s like sex with a dog, sex with a cow; it’s evil’.

We might imagine that Pastor Ssempa can be dismissed as deranged. He is most certainly not representative of most Christian communities and fellowship many of whom are horrified by remarks of this kind. Indeed, Anglican leaders reiterated their opposition to ‘victimisation and diminishment’ of gays and lesbians after David’s death, saying that it was ‘totally against Christian charity and basic principles of pastoral care’. However, we need to keep in mind that this statement was issued at the end of the bi-annual Anglican meeting in Dublin which had been boycotted by the Archbishop of Uganda, the Most Rev Henry Luke Orombi and some half dozen other senior clerics because of disputes within the Anglican communion over same-sex blessings and the ordination of gay clergy. Officially, Archbishop Orombi’s position is that homosexuality is incompatible with scripture and that he supports ‘exclusion from ministry on grounds of behaviour, not orientation’. Like the American Evangelicals, the emphasis is on the reform of gays and the renunciation of sexual acts. The underlying message is that something about these acts threatens marriage, society and children. The implication is that you can be gay – if you must – but something about a homosexual lifestyle is under prohibition, even erasure.

What significance should we give then to President Obama’s attendance this week – with many other congressional leaders – at the National Prayer Breakfast organised by the Washington Fellowship Foundation known as ‘The Family’, and attended by every American President since Eisenhower? The Family is an umbrella organisation for more than 200 ministries in the USA and abroad, and is associated with the congressional prayer groups where lawmakers meet privately for prayer. It also has extensive ties with David Bahati the sponsor of the anti-homosexuality bill in Uganda, and the organiser of the Ugandan National Prayer Breakfast. LGBTI activists and gay and lesbian clergy called on President Obama to say a prayer for David Kato at the breakfast. Freedom of worship and of conscience are important principles in all contexts, so all the more interesting that President Obama chose not to pray for David Kato, instead he made the following statement: ‘We may disagree about gay marriage, but surely we can agree that it is unconscionable to target gays and lesbians for who they are – whether it’s here in the United States or – more extremely in odious laws that are being proposed most recently in Uganda’.

Why did the President feel it necessary to mention gay marriage? A further clue might come from recent antics at the United Nations. In November last year, the Third Committee of the United Nations General Assembly, apparently at the instigation of a number of African and Arab states, voted to remove a reference to sexual orientation from a resolution on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings. Happily, the decision was reversed at a subsequent meeting in December, but commenting on the original vote the Moroccan representative urged all member states to ‘devote special attention to the protection of the family as the natural and fundamental unit of society’.

It’s not just that we need reminding that 76 countries in the world criminalize homosexuality and five consider it a capital crime, but that human rights for members of LGBTI communities are far from secure despite the global expressions of outrage at David’s death. Let’s face it, on the current evidence if you are homosexual then your God-given potential in many parts of the world doesn’t involve having sex or forming a family: not a hope, nor a prayer.